This is the edited text of my Easter sermon at Cottage Church yesterday. The passage was Mark 16v1-8, which you should read before continuing.

What Will You Do with the Empty Tomb?

Think of a time you ran away from something in fear. It could be a metaphorical or a literal running-away. Why did you run?

There are many reasons we flee and fear. Sometimes we’re afraid of getting hurt. Sometimes we’re afraid of losing control. Sometimes we’re afraid of what we don’t understand.

If you’ve ever run away, you’re not alone. A surprising number of people run away in Mark’s gospel. When Jesus drives out a legion of evil spirits from a man, the residents of his village beg him to leave (5v17). When Jesus walks to his disciples on the water they are terrified (6v50). When Jesus is revealed in his glory at the transfiguration Peter, James and John are reduced to a babbling mess (9v6). When Judas the betrayer and his thugs arrived to arrest Jesus in Gethsemane his disciples all deserted him and fled. A young man following Jesus, his tunic caught by the thugs, fled naked—probably the author himself (14v32-52). Peter, fearing that he would die, denied Jesus three times (14v66-72).

Mark’s biography of Jesus ends abruptly with another frightened fleeing. Mary Magdelene, Mary the mother of James and Salome had come to honour the body of the man they had watched die and be buried two nights before. The one in whom they had put all their hopes, the one they believed was sent from God to redeem Israel, was dead. They knew that no dead man could be God’s Messiah; but they came to honour a man who had performed remarkable signs, who had taught them, who had loved them, who had been their friend.

They arrived at the tomb to discover the large stone covering the entrance had been conveniently moved aside. Inside was a young man dressed in white. A living, breathing man is the last thing they expected to find in Jesus’ tomb, and they were unsurprisingly alarmed. ‘Don’t be,’ he says! ‘You are looking for Jesus the Nazarene, who was crucified. He has risen! He is not here. See the place where they laid him.’

Obviously this was not at all what they had expected. Nevertheless, their reaction might seem strange to us. Christ is risen! Surely this is good news. Surely they should be jumping for joy, singing praises, rejoicing! But they have no idea how to understand what has happened. They’re frightened, and they flee.

And so the book ends. There is a longer ending (verses 9 to 20), but this is clearly not part of Mark’s original text. It ties up some loose ends and contains information we have in the gospels of Matthew and Luke. It tells us about Jesus’ appearances to his disciples and others, his commissioning them to preach the gospel to the world, and his ascension to the right hand of the father. It’s the kind of ending we might expect to a book that begins with the words ‘The beginning of the good news about Jesus the Messiah, the Son of God’ (1v1).

But that isn’t the way the book ends. Mark finishes abruptly with the women, frightened and trembling, running from the empty tomb.

We might be so familiar with the story that the strangeness of this ending is lost on us. Here’s a little exercise to help us feel it.

Imagine you were seeing a stage production of Mark’s gospel. Jesus has performed miracles. He’s clashed with religious leaders. He has been betrayed, faced trial, and died. Mary Magdalene and the other women come to the tomb to find it empty. They’re told that Jesus has risen. The women run off stage in astonishment. The curtain comes down. The lights go up.

How would the ending leave you feeling? What would you be talking about with the other theatre-goers as you leave?

You’d leave with unanswered questions. And you’d be talking about what clues the play gave as to what the ending might mean. Who is this man? What has happened to the body in the tomb? Mark’s gospel is a book full of different answers people give to those questions. As we read we are invited to give our own answer. By leaving so many questions hanging as the women run from the empty tomb, Mark is posing those questions to us. Who do you say Jesus is? What do you make of the empty tomb?

While the longer ending might be tidier, Mark doesn’t let us off the hook that easily. He wants us answering those questions on the basis of the story he has told. So the abrupt ending turns us back to the story itself. Can what Mark has written down for us make any sense of the empty tomb?

There’s a clue in the commission the angel gave to the women. They were to tell Peter and the disciples that ‘He is going ahead of you to Galilee, just as he told you.’ The disciples might have responded, ‘What do you mean, “Just as he told us?” When did tell us about anything like this?’

As it turns out, Jesus had spoken about his resurrection clearly on at least three occasions. In chapter 8 we read that Peter and the disciples identify Jesus as the Messiah, God’s promised king. Jesus goes on to tell them that the Son of Man must suffer and die, and that on the third day he would be raised. In chapter 9 he makes the same prediction, and we are told that the disciples ‘did not understand what he meant and were afraid to ask him about it’ (9v32), perhaps because of the tongue-lashing Peter received when he’d asked Jesus about it the first time around (8v31-33)! There is a third prediction recorded in chapter 10 as they approach Jerusalem (10v32-34). On the occasion of the revealing of Jesus’ glory at the transfiguration he had instructed Peter, James and John not to tell anyone about what they had seen ‘until the Son of Man had risen from the dead. They kept the matter to themselves,’ Mark reports, ‘discussing what rising from the dead meant’ (9v9-10).

When we read those verses we often want to shake the disciples by the shoulders. What does rising from the dead mean? It means exactly what it means—rising from the dead! But they didn’t know what it meant, and the women at the empty tomb had not a clue what it was that had happened.

What we need to recognise is that something utterly unexpected and completely new had happened. That’s why Mark draws our attention to the sunrise on the first day of the week. As the sun rises on a Sunday morning to start a new week, so the Son of God rises to new life.

The women at the tomb, though slow to realise what had happened, were right to be astonished by what they had seen. These women stumbled upon something that completely upended the way they understood the world. They wondered what it would mean to believe something that challenged everything they thought they knew. No wonder they were afraid: if what the young man in the tomb said was true, then the whole world had changed, and they had to change, too.

But could they really afford not to believe it?

Mark makes clear all the way through his book that what Jesus is doing is fulfilling the promises of God. He sets this up from the very beginning, quoting from Isaiah 40 and 42, situating this story about Jesus in the exile and promised restoration of Israel. All the hopes of Israel for their nation and for the world were coming to fulfilment in this man Jesus.

But if he was dead, none of it mattered. A dead Messiah was no Messiah at all. As Paul says, ‘If Christ was not raised’ – that is, if he remained in the tomb – ‘your faith is futile; you are still in your sins’ (1 Corinthians 15v17). All that Jesus had promised died with him. And so his disciples and the women who saw him dead and buried despaired.

But if the empty tomb meant Jesus was alive, then everything his followers had hoped for is possible.

If Jesus is risen he really can forgive us our sins; because he is risen he really has made a way for the nations to become part of the people of God; because he is risen he really will return to wipe every tear from our eyes. Indeed, every one of God’s promises is ‘Yes’ in Christ Jesus (2 Corinthians 2v20).

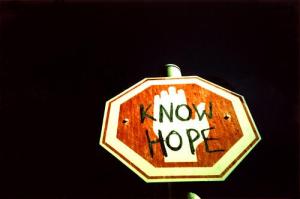

If Jesus lives then hope also lives.

The women went to the tomb to honour a man who had died. Instead they were sent out to proclaim that he is very much alive. Their astonishment came in the moment of realizing that if what the young man in the tomb said was true then their hope had been restored.

The story Mark has told us about Jesus is the story of the salvation of the world. His open ending invites you to become a part of that story ourselves. How will you respond? Will you run in fear, unable to face a God who presents such a challenge to our understanding? Or will you come to the empty tomb and find your hope?

It’s all too easy for us to think we understand the resurrection. But if we face it as those women did on Easter morning we see that it challenges everything we thought we knew. How can the empty tomb be possible? Their witness reminds us that God is greater than we ever imagined. Their fear should remind us never to imagine we’ve got our heads around God. In Christ’s resurrection he has done something utterly new. It changes the world.

So whatever your hopes are—for reconciled relationships, for healing from illness and emotional hurts, for the very restoration of the world—they are found in the empty tomb. For God has reconciled everything to himself by making peace through the blood of the cross, and that crucified Lord, the firstborn from the dead (Colossians 1v15-20), is the beginning of new creation.

Today we celebrate the resurrection of the one Mark calls the Messiah, the Son of Man, the Son of God. We like the women must tremble with amazement when we come to the empty tomb. Christ is risen! How wonderful that we may meet the living Lord.